Since lockdown was imposed in Wuhan, China on the 23rd January 2020, a ripple of concern waved through the financial markets with the CSI 300 Index (an aggregate measure of the top 300 stocks in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges) dropping almost 9% GDP (Gross Domestic Product) by 3rd February 2020.

This rare pandemic has caused havoc in our day-to-day lives, agitated markets, and swiftly pushed economies to the edge of ruin. Unfortunately, no economy was immune to any of the fallout, and the pandemic has had a domino effect across the world except for Antarctica. It’s the only country not to have any reported cases, and there is no economic activity at present there. It wasn’t long before countries all over the world followed suit, imposing their own lockdown rules, followed by drops in their domestic market.

How is the world doing economically?

In the past 21 days, several countries, including the UK, have declared that they are experiencing a technical recession, most recently Germany, and Japan - the world’s third-largest economy. Japan’s economy shrunk 0.9% in Q1-2020 compared to Q4-2019, an annual pace of 3.4% in the first three months of 2020. Japan was already dealing with existing economic struggles in 2019 including the aftermath of Typhoon Hagibis, a powerful storm that hit the country last Autumn.

The Bank of France governor, François Villeroy de Galhau, stated that lockdown in France would result in a six-point GDP drop in the first quarter of 2020, but added that there was a promising slight rise in April in comparison to March. Across the pond, in the US, Deutsche Bank updated its US GDP expectations and stated we would see a 40% drop in the second quarter, in comparison to earlier predictions where they forecasted only a 13% drop, having dropped 4.8% in the first quarter of 2020. The Australian Reserve Bank predicts that there will be a 10% recession in Australia during this year.

The European Commission stated that the economic output in the first quarter of 2020 in Europe is set to be almost 16% lower than in the last quarter of 2019. It forecasts that this year, the contraction in EU GDP is expected to be 7½%, far deeper than the drop during the 2008/9 financial crisis.

What is happening in the UK, and are we experiencing a recession or a depression?

Recessions only happen when there is a widespread decline in economic activity.

Different countries have varying semantics around defining a recession, although many carry the same sentiment. The UK defines a recession as ‘negative economic growth for two consecutive quarters’. Although recessions are temporary, they can have a long-lasting effect that can be felt for years. A depression, however, is an extended recession that has years, not quarters, of economic contraction.

Since 1900, the UK has had eight recessions including the current one, and two depressions. Covid-19 is the trigger for the current recession, exacerbated by the 2020 Russia-Saudi Arabia oil price war and international travel bans. This is the only time in the UK since 1900 that a recession was triggered by a pandemic.

If we take a step back and look at previous UK GDP figures as a comparison; UK GDP as a whole in 2019 showed growth by 1.4% from 2018 (although it was noted by the Office for National Statistics that that was one of the slowest rates since the financial crisis of 2008/9). In the first quarter of 2020, UK GDP decreased by 1.6% in comparison to the first quarter of 2019, the biggest fall since the fourth quarter in 2009, when it also fell by 1.6%.

So is the UK in a recession? Alan Wheatley, global economy and finance associate fellow at Chatham House tells us: “It is a recession, that goes without saying. It is a massive catastrophe.” Two consecutive quarters with a decline in GDP puts the UK solidly at the start of a recession.

Timeline

- 9th March 2020: 15 deaths in the UK attributed to Covid-19.

- 11th March 2020: The UK Government’s Chancellor, Rishi Sunak has delivered his budget amidst the continuous drop across global markets. He originally promised a £12 billion package to small businesses in the UK Spring Budget, a small amount compared to his renewed offering six days later.

- 17th March 2020: Sunak unveiled an unprecedented £330 billion of help in the form of the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS) - the biggest bailout package ever created in the UK. Read more about it on our blog.

- 23rd March 2020: Lockdown begins in the UK.

- Mid-April: The UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) warned that the pandemic could see the UK economy shrink by a record 35% by June 2020.

- 20th April 2020: Over 140,000 UK companies by this point have applied for the coronavirus job furlough scheme. Eligible businesses can have up to 80% of a furloughed worker’s pay reimbursed by the UK government.

- 4th May 2020: HM Treasury announced that small businesses will be able to apply for Bounce Back Business Loans (BBLS) without the lender asking for a personal guarantee, plus the loans are 100% government-backed (the two main differentiators to the CBILS). You can find more information here.

- 7th May 2020: The Bank of England forecasts a 25% contraction in the current quarter, and that the UK economy could shrink by 14% this year.

- 12th May 2020: Sunak announces that the UK coronavirus furlough scheme will be extended until October.

- 13th May 2020: It was reported that the UK was dealing with a recession as the economy shrank by 2% in the first quarter of 2020. Data from the Office for National Statistics reveals that the decline in output in March has caused the sharpest three-month contraction since the financial crisis in late 2008.

Why is the recession in the UK being touted as much worse than the Great Depression of 1930, and the 2008/9 Global Financial Crisis?

In 2008, the UK economy had moved into a technical recession in the third quarter as GDP fell for a second successive quarter, and continued to fall for six consecutive quarters. The UK economy finally moved out of recession in the last quarter of 2009. This means that the Global Financial Crisis, triggered by a depreciation in the subprime mortgage market in the US, followed by the collapse of the investment bank Lehman Brothers which turned the situation into an international banking crisis, took the UK over a year to get back onto the road to economic recovery.

The World Economic Forum wrote in April, “With each passing day, the 2008 global financial crisis increasingly looks like a dry run for today’s economic catastrophe. The short-term collapse in global output now underway already seems likely to rival or exceed that of any recession in the last 150 years.”

The 1930 Great Depression, the longest and most widespread depression of the 20th century, lasted just under a decade. It started on a day now known as Black Thursday when 16 million shares of the stock were quickly sold by panicking investors who had lost faith in the American economy. Only a few countries started to recover by the mid-1930s, but globally it would take until the late 1930s for economies to get back onto steady grounding.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) stated: “This makes the Great Lockdown the worst recession since the Great Depression, and far worse than the Global Financial Crisis. Recovery in 2021 is only partial as the level of economic activity is projected to remain below the level we had projected for 2021 before the virus hit. The cumulative loss to global GDP over 2020 and 2021 from the pandemic crisis could be around 9 trillion dollars, greater than the economies of Japan and Germany, combined.”

As a comparison to the IMF’s figures, global GDP fell by 4% in the 2008/9 Financial Crisis which is equal to around a $2 trillion loss in global economic growth.

Economists are struggling to predict the endgame of this crisis. Markets around the world are optimistic that a recovery will be fast, perhaps starting in the fourth quarter, but this is as suggested before, optimistic.

Wheatley tells us: “Although interest rates are very low, there is a lot of monetary and fiscal stimulus going into the economy, and the UK Treasury has done absolutely the right thing by supporting incomes, I still think that people who are expecting a swift recovery are making some heroic assumptions. It will take much longer than a quarter to recover. It will be a very slow recovery because there is every chance there will be a second peak of infections. Furthermore, we have the shadow of Brexit which generates an uncertain future”.

So how do we regain financial prosperity?

Short-term, many countries quickly implemented ideas and initiatives into place to help those in need to get through the worst of the pandemic.

In France, the head of the French Central Bank suggested that they should print more money to hand to companies to combat severe deflation. In the US and Hong Kong, the governments have launched schemes to distribute money directly to citizens to help them survive throughout the pandemic (although the length of time that this distribution of money will go on for is undetermined). In the UK, the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS) and the Bounce Back Loan Scheme (BBLS) have been both lauded and met with disdain as small businesses, who contribute greatly to the UK economy, continue to struggle to get finance.

To weather this storm long-term, the UK government has put in all of their efforts to get people back to work as of the 20th May to start bandaging the economic downturn. This will do little short-term, as pandemic shock to the public and to global investors who saw the UK as a strong economic hub (the UK is the sixth-largest economy in the world) will not be solved overnight.

Governments will need to work on long-term investment to rebuild businesses and paths to international trade. They also need to reignite public trust. People need to feel safe to work and leave the house to nurture a world outside of a digital marketplace (galleries, museums, restaurants, clubs, bars etc). Although this pandemic has changed the way we consume technology, nothing compares to a real life experience.

Beyond finding a vaccine to help with the health challenges faced now, there’s no one size fits all solution for the world economically. Increased spending is directly influenced by societal norms and emotion, and there’s no doubt that the pandemic has changed the mood globally.

Wheatley says: “There won't be a return to normal. First, a lot of people will be nervous about going to crowded places - think about pubs and football matches, theatres and cinemas - there will be an automatic drop in activity. Secondly those industries could take a long time to get back to what was considered normal. Profit margins were already slim, and rent was high, these places were struggling before, and may continue to do so. There will be structural changes to our economy, some areas will see an economic boost, for example, Zoom and other digital, contactless services, but there will be fewer people travelling by train in the future and shopping in the high street. There will be a lower demand for office space because more people will adapt to working from home”.

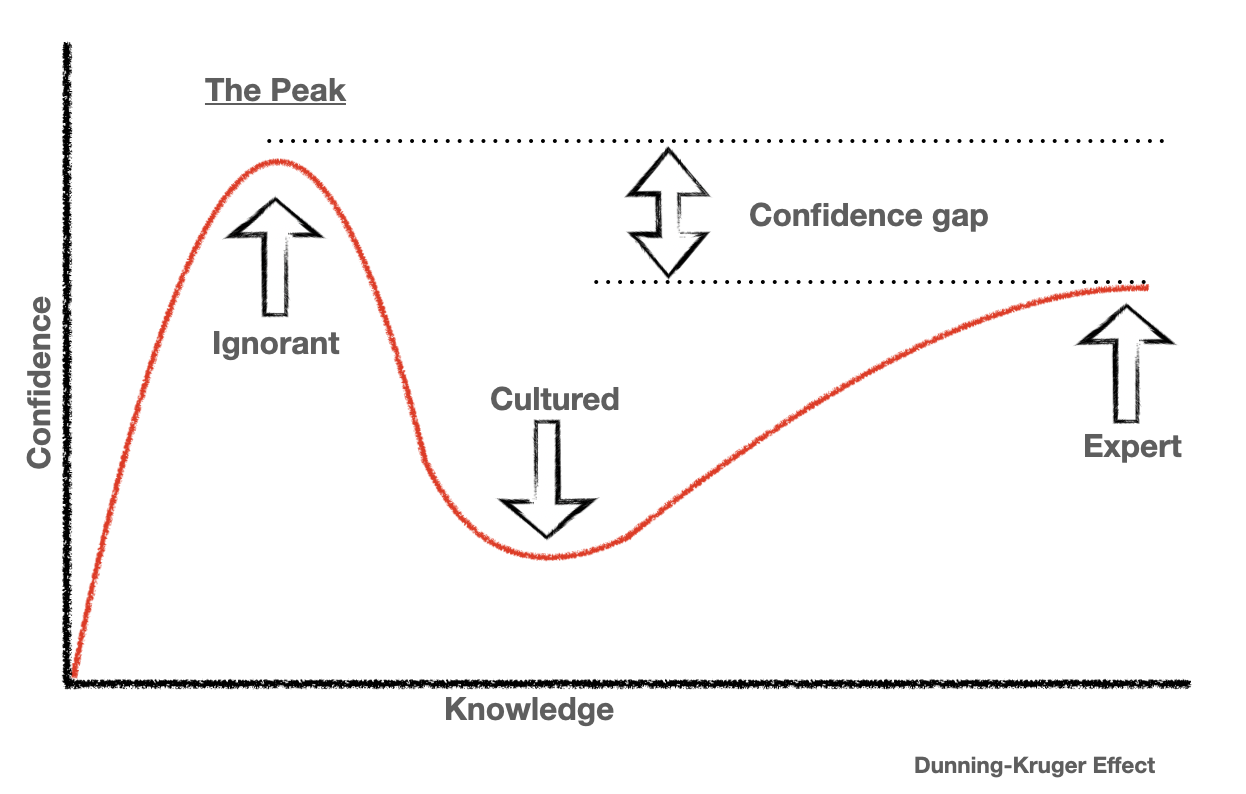

Furthermore, spending money is not only practical, but emotional. We’re all susceptible to the availability bias, which is where information that is close at hand is top of mind. With news cycles and social media feeds full of Covid-19 doom and gloom, those attitudes will be reflected in consumer spending and sentiment. While there’s expected to be pent-up demand for certain consumer goods and services as restrictions ease, it’s still unclear how that demand will compare to pre-pandemic spending levels.

Meadhbh Hayden, tomato pay's Behavioural Scientist, who previously worked at Ogilvy Consulting tells us, “The levels of uncertainty in this crisis are unlike anything we’ve seen in previous economic downturns. Humans have a strong preference for the known risks over the unknown, and Covid-19 has created many new risks for consumers and businesses alike to navigate. What we do know is that recessions provide the perfect storm to drive changes in consumer behaviour and habits. Companies like Uber, AirBnB and Stripe were founded during the last recession and have since totally disrupted their respective industries. The question now becomes what industries are now ripe for disruption, and how do companies leverage this ‘new normal’ to bring us out of this downturn.”

Some light at the end of a seemingly long tunnel

UK businesses may see new opportunities arise as the country rediscovers it’s love for shopping locally. Small businesses have been providing essential services and products to local communities over the past few weeks and filling the gaps where we may have sought products elsewhere. Our lack of ability to travel far has forced us to look closer to home for what we need.

UK industries might also get a boost. Manufacturing is an example of an industry that could grow after this pandemic, with many businesses looking to localise their supply chain to mitigate dependence on global supply chains that could also supply some much needed employment.

A silver lining to an otherwise storm cloud in this pandemic, is a side effect of the ‘new norm’ of social distancing. Many businesses have gone cashless, prompting a rise in the contactless spending limit, and an increase in the use of digital payment methods which looks set to continue. The necessity to use safer, non-physical, and tactile ways to make payments is creating a new wave of payment solutions, making it a promising industry that will adapt well to the duration and aftermath of the pandemic.

The IMF wrote: “Assuming the pandemic fades in the second half of 2020 and that policy actions taken around the world are effective in preventing widespread firm bankruptcies, extended job losses, and system-wide financial strains, we project global growth in 2021 to rebound to 5.8 per cent.”

As we have seen in the years following the most recent global recession in 2008/9, economies will grow again, and many countries will see positive, albeit slow growth year-on-year across many industries.

We will all have to sit patient as it will take time to see the financial boom felt pre-coronavirus, and trust in the world’s ability to create new business opportunities when forced to pivot in such trying times.