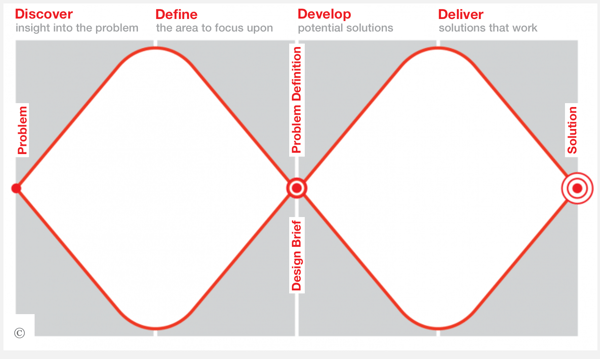

Talk to any product owner and they’ll be familiar with the ‘double design’ framework. It’s a tried and tested process in design thinking. It has many advantages, such as, allowing divergent thinking before focusing back to the challenge at hand. It’s also flexible enough to incorporate other frameworks or processes within each stage.

In this article I’d like to discuss some of the behavioural tools that can fit into the double diamond design process that can help product designers ensure they’re leveraging behavioural science at each stage of product design.

The Double Diamond Design Process © British Design Council

Discover

In this first stage, you have the opportunity to completely diverge to try and understand everything about your users, their wants and needs.

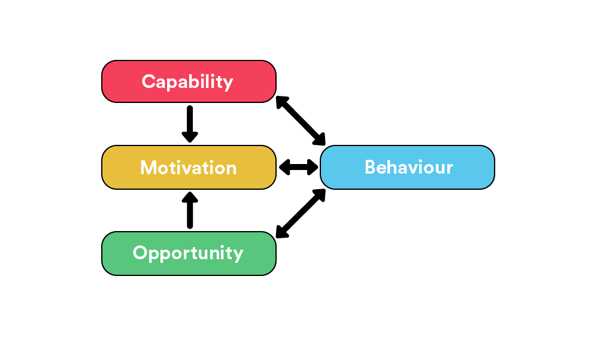

Ensuring you use a behavioural research framework like COM-B (source 1 in footnotes) is a comprehensive way to correctly identify your users’ drivers and barriers to behaviour. This will help you to prioritise your behavioural challenge.

COM-B looks to the three key components of behaviour; capability - whether you’re able to carry out the behaviour, opportunity - whether your environment and social group enable you to engage in the behaviour, and motivation - whether you’re either consciously or unconsciously interested in carrying out the behaviour.

COM-B is frequently used for public health challenges such as tackling obesity or encouraging people to give up smoking, but it is as equally effective in diagnosing a behavioural challenge in the private sector.

COM-B framework for understanding behaviour

The discovery phase is also an excellent opportunity to apply some lateral thinking. We are all usually aware of what is going on within our industry - what our competitors are up to, where thought leaders think innovation will come from, what problems customers have said they want solved. However, we rarely take the time to look beyond our own bubble. In doing so we can miss out on some valuable lessons. By defining challenges as behaviours, and not just industry-specific problems, we can be inspired by so much more.

For example, Tesla may be worried about customers feeling confident using their self-driving cars. Tesla could learn from the adoption of the Betty Crocker cake mix. Tesla could adopt a lateral thinking approach and research around the actual behaviour (confidence) instead of the product (self-driving cars). When Betty Crocker first launched its cake mix, where you just had to add water before baking, it wasn’t a success. Through research, they discovered this was because those using the mixes felt like they were ‘cheating’ and not making a proper cake. In the end, they took the eggs out of the mixes, forcing people to add an additional ingredient. This increased the emotional investment made in a Betty Crocker cake, and sales of the mixes skyrocketed. Perhaps the IKEA effect may be just as relevant for Tesla in 2019 as it was for Betty Crocker in the 1950s.

Define:

Take some time here to refine the actual behavioural challenges facing your users - can you express the problem statement in terms of actual human behaviours? Keep the focus on action verbs - for example, instead of a broad ‘increase engagement with our app', Amazon might define their behavioural challenge as, ‘encourage users to do at least three searches per month’.

Creating these behavioural challenges forces you to design for your end users and their needs, not just what you or management think the user wants. And don’t forget to nudge yourself - write it on a post it note on your desk, pop a calendar invite in and revisit these challenges once a week.

Develop:

Now is your chance to actually ideate and create your product. Here you have some great behavioural frameworks at your disposal to really get your creative juices flowing. Some of the more accessible, but still powerful, frameworks include EAST and MINDSPACE. Ask your neighbourhood behavioural scientist and they’ll easily tell you the key principles to help you focus on to address your problem.

Another point to consider is whether you want your users to engage with your product as a habit. There are several great habit formation models, from BJ Fogg’s Behaviour Model, to the Habit Loop from Charles Duhigg. Consider whether it would be worthwhile running a habit formation workshop with your team to ingrain these features into the product from the start.

As your product goes through the development cycle, make sure to return to those behavioural challenges you defined earlier to ensure you’re trying to solve these above anything else. It’s easy to veer off-piste, assuming you know the needs and wants of your users at this stage. Your users will reap the benefits later if your whole development team stays focused.

The final point to consider before moving on to delivery is how you will measure the success of the product. Take this opportunity to ensure you build experimentation as the default within your product. Even with all the research and user feedback in the world it’s often impossible to say exactly which design or feature is most likely to drive usage.

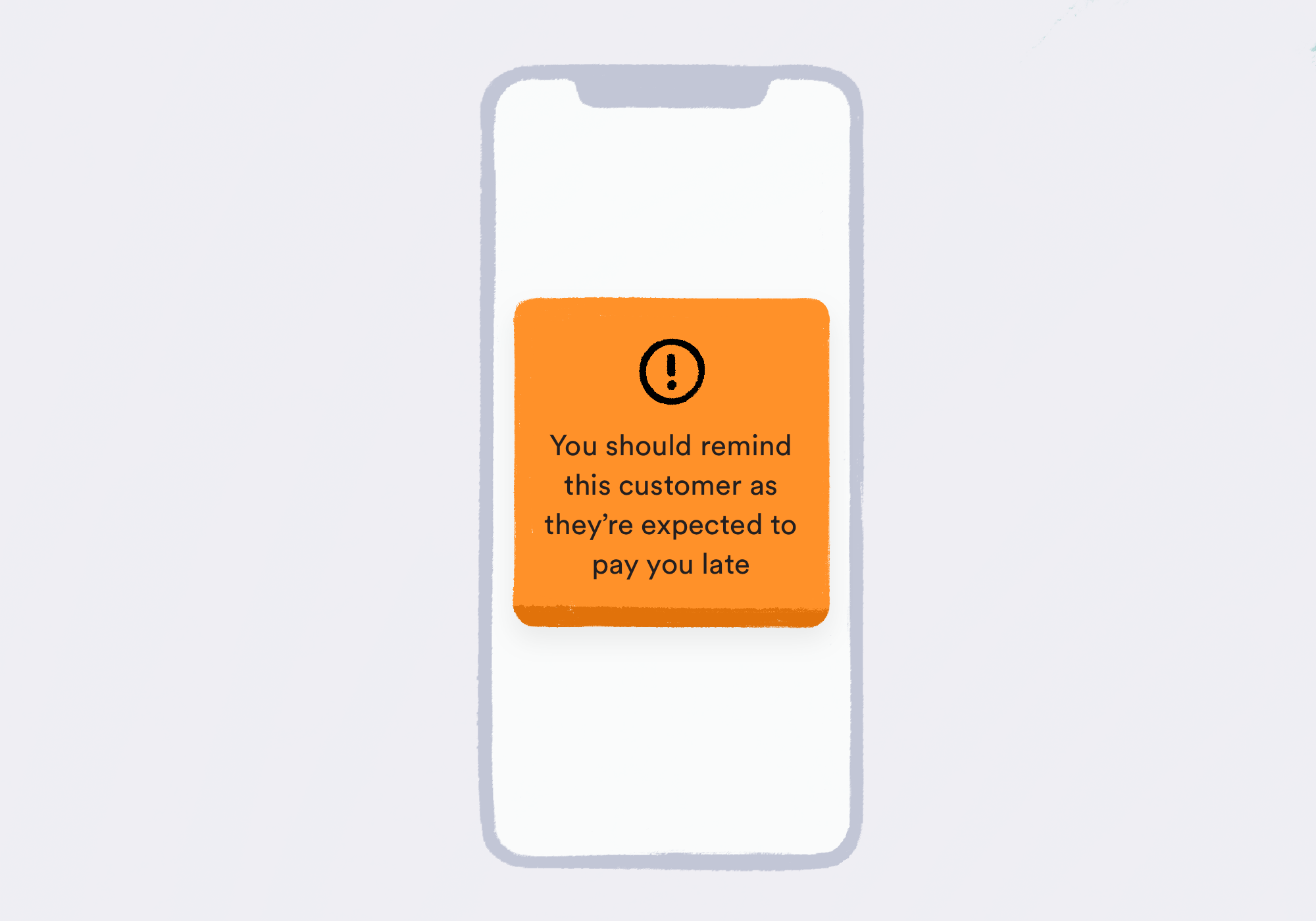

Deliver:

Congratulations on delivering your product!

As you enter the iteration phase of product development, keep in mind those behavioural challenges. Are they solved? If not, are there any new technologies or solutions that weren’t available before that could help you solve them for your users? If yes, do you know why your product is working? Do further testing with users, and keep to your experimentation plan - iterating constantly. Don’t be afraid to test some of your more counterintuitive ideas, you may find something unexpected clicks with your users and drives more engagement than the most logical approach.

To find out more about how tomato pay uses behavioural science ethically, contact us.

Source one: Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42.